*All reviews contain spoilers*

Disclaimer: This blog is purely recreational and not for profit. Any material, including images and/or video footage, is property of their respective companies, unless stated otherwise. The author claims no ownership of this material. The opinions expressed therein reflect those of the author and are not to be viewed as factual documentation. All screencaps are from Disneyscreencaps.com.

Cast –

Joe Baker – Lon

Christian Bale – Thomas

Irene Bedard – Pocahontas (speaking)

Billy Connolly – Ben

Jim Cummings – Powhatan and Kekata (singing voices)

James Apaumut Fall – Kocoum

Mel Gibson – John Smith

Linda Hunt – Grandmother Willow

John Kassir – Meeko

Judy Kuhn – Pocahontas (singing)

Danny Mann – Percy

Russell Means – Powhatan

David Ogden Stiers – Governor Ratcliffe and Wiggins

Michelle St. John – Nakoma

Gordon Tootoosis – Kekata

Frank Welker – Flit

Sources of Inspiration – The life and legend of Powhatan teenager “Pocahontas” (whose real name was Matoaka), who lived from c. 1596 – 1617 and died in London, England. This marks the first Disney classic to be based on real history (however loosely).

Release Dates –

June 10th, 1995 in Central Park, New York City, USA (premiere)

June 16th, 1995 in USA (limited release)

June 23rd, 1995 in USA (general release)

Run-time – 82 minutes

Directors – Mike Gabriel and Eric Goldberg

Composers – Alan Menken

Worldwide Gross – $346 million

Accolades – 15 wins and 6 nominations, including 2 Oscar wins

1995 in History

The global population at this time is over five and a half billion people

The World Trade Organisation is established

The Great Hanshin Earthquake kills over 6,000 in Japan’s second-worst earthquake of the century

The infamous O. J. Simpson court trial spans most of the year in the USA; Simpson is acquitted

Kevin Mitnick is arrested by the FBI after hacking into top secret US computer systems

The first Yahoo! Search interface is founded

Mississippi becomes the last US state to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment to the US constitution, which was nationally ratified in 1865 and approved the abolition of slavery

The Schengen Agreement goes into effect in Europe, easing cross-border travel

Popular Mexican-American singer Selena Quintanilla-Pérez is murdered by her former employer, Yolanda Saldívar

The Samashki massacre occurs as part of the First Chechen War, with Russian troops massacring over 250 civilians

Rox becomes the first TV series to be distributed via the internet

Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols cause the Oklahoma City bombing in the US, killing 168 people; McVeigh is later executed, while Nichols is imprisoned for life

Gedhun Choekyi Nyima is proclaimed the eleventh incarnation of the Panchen Lama by the Dalai Lama; the six-year-old is promptly taken into custody by Chinese officials and has never been seen in public since (although he’s said to be living an ordinary life)

Shawn Nelson steals a tank from an armoury and goes on a rampage through San Diego with it before being shot by police

Actor Christopher Reeve is paralyzed in a horse-riding accident; he never walks again

The death penalty is abolished in South Africa

France briefly resumes nuclear testing in French Polynesia, continuing until early 1996

The Sampoong Department Store collapses in South Korea, killing 502 in the deadliest modern building collapse before 9/11

Over 8,000 Bosniak civilians are killed in the Srebrenica massacre in Bosnia and Herzegovina

On the Caribbean island of Montserrat, a series of eruptions from the Soufrière Hills volcano begin which continue to this day; about two thirds of the islanders have evacuated

Tensions rise between China and Taiwan during the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis

Just months after becoming the first woman to summit Everest without supplementary oxygen, climber Alison Hargreaves is killed in an avalanche

Microsoft releases the Windows 95 operating system

Online retailer eBay is founded

French woman Jeanne Calment becomes the oldest person ever recorded at 120; she lived for a further two years and her record still stands today

289 people are killed in the Baku Metro disaster in Azerbaijan, the world’s worst metro disaster

The Indian city of Bombay is officially renamed back to Mumbai

The Dayton Agreement ends the Bosnian War, but the wider Yugoslav Wars it was a part of continue

Serial killer Rose West becomes only the second woman in British legal history to receive life imprisonment, after Myra Hindley

Pixar releases the first ever entirely computer animated film: Toy Story

The medium of cinema celebrates its centenary

Births of Tom Glynn-Carney, Gigi Hadid, Troye Sivan, Kendall Jenner and Ross Lynch

As we come to the halfway point of the Renaissance, we find an extremely loaded film called Pocahontas. Now, this one isn’t a bad film per say – it is part of the Renaissance after all – but most Disney fans think of it as the “turning point” after which the quality and performance of Disney films became more mixed. (Debatable, to say the least). Some have even partly blamed this film for the eventual decline in traditional animation which followed a decade later, due to it being outperformed by the computer-generated Toy Story in the year it was released. Poor Pocahontas had so much piled on its shoulders that it ultimately collapsed under the weight, but they were trying so hard to make it great that some parts of it do actually hold up. Before we get into the nitty gritty of it, though, let’s back up and get some context.

The idea for a film about the life of Pocahontas was born at a Thanksgiving dinner in 1990, when The Rescuers Down Under director Mike Gabriel was batting about various potential projects involving Western legends like Annie Oakley, Buffalo Bill and Pecos Bill (the latter had already been done, back in the Package Era). Ultimately, he settled on Pocahontas and pitched the idea to the Disney executives in early 1991, by writing the title “Walt Disney’s Pocahontas” on an image of Tiger Lily from Peter Pan (1953). On the back of the image, he taped a brief pitch that read “A beautiful Indian princess falls in love with a European settler and is torn between her father’s wishes to destroy the settlers and her own wishes to help them — a girl caught between her father and her people, and her love for the enemy.” (Even from the beginning, the story clearly did have a lot of potential).

As it happened, the Feature Animation department’s president at the time, Peter Schneider, had been trying to develop a version of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and he spotted the similarities between his idea and Gabriel’s pitch. Schneider later said “We were particularly interested in exploring the theme of ‘If we don’t learn to live with one another, we will destroy ourselves.’” The LA riots of 1992 further convinced them to commit to this racial angle, as it felt like a timely message for nineties audiences.

Into this blossoming production walked Jeffrey Katzenberg. In the wake of Beauty and the Beast’s surprise success with its Best Picture nomination at the Oscars, Katzenberg was excited and decided the time was ripe to create another romantic epic in the hopes of securing an actual Best Picture win. The only trouble was that the studio’s two current projects at the time – Aladdin and The Lion King – were both too far into development to be changed so drastically, so it seemed that Pocahontas was the only viable candidate. The film was therefore retooled from a historical adventure about overcoming racial prejudice into Katzenberg’s dream drama; the heroine was aged up, making her love for John Smith less innocent and more of a mature relationship, and the comic relief animals lost their voices in an attempt to make the film more “serious.” That right there was almost certainly the film’s biggest problem from the start; it was always going to be a highly sensitive topic because it was based on real history, but adding the pressure of winning a very prestigious award placed a lot of restrictions on the creative team and made it difficult for them to do their jobs effectively.

As well as Gabriel, that team also included Eric Goldberg, who joined the project as co-director, Michael Giaimo as the art director and Alan Menken and Stephen Schwartz doing the music. Octogenarian Disney legend Joe Grant also made his return to Disney after many years’ absence to work in the story department (which was headed by Tom Sito).

To their credit, the team did do plenty of research and took a trip to Jamestown itself in June 1992, as well as making excursions to many other nearby sites in Virginia which made up the Tsenacommacah (the historical homeland of the Powhatan people). The 1992 trip included a visit to the Pamunkey Indian Reservation and interviews with historians at Old Dominion University, as well as consultations with Native American leaders in the area. Later, other Native American consultants were brought in to authenticate details like the clothing and choreography of the war dance. The film’s producer, James Pentecost, even had them meet actual descendants of the Powhatan tribe which Pocahontas herself had belonged to.

One of these was Shirley Little Dove Custalow-McGowan, who put a lot of time into the project and travelled to the Disney studios in California three times. Although she offered her services for free, Disney did pay her $500 a day as a consulting fee plus expenses. After a while, though, it became clear that the filmmakers weren’t sticking as closely to history as McGowan had hoped, leading her to remark, “This is a nice film – if it didn’t carry the name Pocahontas. I wish they would take the name of Pocahontas off that movie. Disney promised me historical accuracy, but there will be a lot to correct when I go into the classrooms.”

The screenplay was begun by Carl Binder in January of 1993; he was later joined by Susannah Grant and Philip LaZebrik. The finished script took eighteen months and fourteen drafts to complete – Grant wrote to a specific story outline while working on the film and no scene was rewritten less than thirty-five times until she felt it was perfect.

All of this just illustrates how tough this production was on the people involved. They had so many people to please and the executives were too ambitious for their own good; although Pocahontas was known as the “A” project to Lion King’s “B” project and many animators fought to transfer across from the latter to the former, Eric Goldberg actually did a little work for Chuck Jones Productions under the pseudonym “Claude Raynes” during production just to get a break from the stifling atmosphere of Pocahontas. As one popular anecdote goes, the paranoia of the management got to the point where they criticised animators for drawing the animals (Meeko and Percy) wearing the clothing of their respective human groups, with someone saying “Animals don’t have the intelligence to switch their clothes! They don’t even have opposing thumbs.” Wait… what? “Don’t have the intelligence”? Mate, animals don’t typically wear clothes, why are you worried about intelligence? Needless to say, that particular concept did make it into the final film, but it just goes to show how frightened of failure the executives had become. In a way, the string of mega-successes they’d had in the years prior to Pocahontas had become a sort of curse; they’d set such a high bar for themselves that they were now breaking their backs trying to reach it.

Still, as I said, some things about Pocahontas do work nicely – it’s just that it’s a frustrating film to watch because you can sense the potential it had, if only it hadn’t been jumping through hoops trying to be so many things at once. Let’s take a look at the individual elements of it to see if we can work out why it had such an underwhelming reception.

Characters and Vocal Performances

Casting for the film began in September of 1992 and this time, unlike with their last two productions, Disney stressed that they were looking for actors of the appropriate ethnic origin for the parts, in this case Native Americans. With the characters of John Smith and Pocahontas, Disney would be creating their very first interracial romance.

Funnily enough, it turned out that three actors from the film were also involved with other Pocahontas-related projects: Gordon Tootoosis played Chief Powhatan in Pocahontas: The Legend (1995), while Christian Bale and Irene Bedard went on to play John Rolfe and Pocahontas’s mother, respectively, in Terrence Malick’s epic The New World in 2005.

Now, it has to be said that the portrayal of Native Americans here is leagues ahead of what we saw in Peter Pan…

Seriously, leagues. However, taken as a whole, there are two recurring problems with the characters of this film: underdevelopment at the writing stage, and lacklustre vocal performances at the acting stage. These two issues affect almost all of the characters in the film, including the leads and the villain. It’s a distracting and disappointing situation, but either way, let’s take a closer look.

For the lead role, Judy Kuhn was actually cast before Irene Bedard and was originally set to voice the entire part. However, the search for a speaking voice continued and Bedard was found by the casting director while she was filming Lakota Woman: Siege at Wounded Knee (1994). She later said that she took a train to Buffalo in New York and walked into the audition wearing a sundress and straw hat, before returning to the set of Lakota Woman and finding out there that she had gotten the part.

Now, we’ve seen a lot of great heroines in the last few films, but there’s one thing that sets Pocahontas apart from them which I genuinely feel guilty about bringing up – in the words of Mel Gibson, “Pocahontas is a babe”. I’m sorry, I don’t usually focus on that kind of thing when discussing any character, but dayum. Just look at her! Even Jasmine’s got nothing on this girl. Goodness knows what the actual Pocahontas would think if she could see what Disney did to her here; from her silky curtain of raven-black hair to her toned and curvaceous figure, standing almost as tall as the hero, this version of Pocahontas exhibits a degree of physical perfection so absurd that it becomes the most memorable thing about her. Much like Aladdin, she seems to have been “aged up” on purpose to add a little sex appeal – there, Michael J. Fox became Tom Cruise, while here, a little girl has blossomed inexplicably into Naomi Campbell. We’ll get into this a little more in the Animation section, but I couldn’t open this discussion without bringing it up. It feels so distracting; even when earlier Disney girls had “sexy” moments, they still retained distinct personalities and were rarely made to feel like objects to be admired (possibly excepting Aurora).

Disney’s Pocahontas beside an engraving of the real one by Simon de Passe, 1616

The trouble with Pocahontas is that her looks become the focus, because her personality is so dull – much like the film she’s a part of, she’s all surface glamour with little depth. The filmmakers apparently enjoyed working with her a lot and considered her character a strong one, so it’s a real shame that the final result of all their efforts feels so flat. Things start out alright at first; in her early scenes she’s presented as playful and mischievous, reflecting her nickname – “Pocahontas” means “little mischief”. (It’s a pity the filmmakers didn’t use her proper name, Matoaka; it’s not that hard to pronounce). We see her having fun with her friend Nakoma and making sarcastic cracks about Kocoum’s “seriousness,” as well as enjoying a thrilling canoe ride down some rapids. She feels younger and lighter in these early scenes, more carefree and more enjoyable to watch.

However, even at this point, there are problems with the character – unlike the earlier heroines, her aspirations are rather vague and she doesn’t seem to know exactly what she wants. Her “I Want” song is reminiscent of Belle’s, but this time it’s even vaguer – all Pocahontas seems to want is a chat with Sigmund Freud! This is perhaps one of the downsides of making her older; there’s no room for teen angst or self-discovery, because she’s already a young adult who knows her place in her society and is, for the most part, quite content among her people. Until the colonists arrive, her only goal seems to be to avoid marrying Kocoum, who for some reason is not to her tastes. In earlier drafts of the script, their relationship was explored in more depth and we would find out that Pocahontas feels stifled by her “traditional” husband because she’s a free spirit longing to explore and have adventures, but little of that remains in the final film.

Once the colonists do arrive and she meets John Smith, she quickly becomes as “serious” as she criticises Kocoum for being. There’s a real irony to this because, as I discussed in the intro, the filmmakers were trying to make this film a more “serious” drama in order to win favour with the Academy again, so most of that mischievous spark we glimpse in Pocahontas’s early scenes is wiped out by the second act, to be replaced with lots of smouldering poses and concerned expressions. It doesn’t help that her love interest is even duller than she is, but we’ll get to him in a minute.

The best I can say of her in her first few interactions with John Smith is that she demonstrates admirable self-respect, refusing to allow him to speak to her like an imbecile – I really love the way she shuts him up when he’s bandying words like “savage” about, making it clear that she won’t be patronised. That said, the relationship between them is not one of Disney’s strongest. When I look back at Belle and the Beast or Aladdin and Jasmine, I find much more believable chemistry than we see between these two dullards. Their attraction doesn’t seem to have any solid basis; I mean, what do they have in common? Colours of the Wind is the specific sequence where the “romantic” feelings come in, so perhaps the bond is due to… nature? Did they listen to each other’s hearts? Who knows! Unfortunately, the other member of this love triangle, Kocoum, is yet another underdeveloped personality and it’s difficult to root for him, either – with films like Brave and Moana championing the independent woman nowadays, I can’t help wondering whether it would have helped this film to not have a romance at all.

Pocahontas does have the odd moment where you can sense the kind of engaging character she almost was; throughout the film, she displays some vague shamanistic skills like the auto-translation of English and the ability to communicate with both animals and trees, but none of this is ever fully explained and ends up feeling like half-baked “magic.” Pocahontas also seems to know her medicines, as we see when she gives Smith some willow bark to “help with the pain” after he’s been shot – Native Americans actually did chew willow bark to relieve pain, because it has been proven to contain salicylic acid (the basis of Aspirin). However, she’s rarely allowed to really shine and doesn’t have any particularly memorable moments outside of the musical numbers.

The big climax culminates in that famous image of Pocahontas throwing herself across Smith to protect him from execution at the hands of her father, and I must admit I like how this scene is handled – her bold cry of “I won’t!” when told to stand back is well-delivered and powerful. However, even here, the moment is diluted somewhat because of the presence of the “romance”; why could they not have kept Pocahontas younger, thus making the act more symbolic and less about personal interest?

There’s a lot of debate among historians about the authenticity of the real John Smith’s story about the ceremony where Pocahontas is said to have “saved” him, but it’s still widely accepted that she was popular with the colonists because she was a good mediator between the two sides, gifted with wisdom and strength beyond her years. In this film, she’s simply rescuing him because she loves him and while that in itself is fine, it’s not quite as powerful as the original message of peace and acceptance that the character was going to promote. It feels like she’s lacking in autonomy; the decision to save Smith is tied up with a lot of “dream” mumbo-jumbo and is presented as her “path” or fate, rather than a choice she makes of her own accord. (Again, this is something that is done much better in Moana – I’ll come back to the similarities between these two films in Plot).

Ultimately, although she is determined and committed to making peace, Disney’s Pocahontas feels like a bit of a step back for female leads. By the end of the film, she hasn’t really changed – she even chooses not to accompany Smith back to England, which feels out of character considering the fact that she was longing for adventure earlier on (although I actually do like the ending, which I’ll also come back to in Plot). Underdeveloped, uninteresting and rather preachy, Pocahontas is a bit of a disappointment – and no amount of good looks can fix that.

Speaking of good looks…

You know what the guy actually looked like? Here he is:

For the role of the colonist John Smith, Sean Bean was apparently being considered (why couldn’t they have used him, that might have been great!), but in the end, it went to Mel Gibson. What a strange casting decision! Even back then, he’d had his share of controversies and there was much more to come in the years ahead, so having him as the lead in a Disney film feels a bit, well… awkward. His performance is rather stilted, making you wonder how much he was really enjoying this (although to his credit, he did do all his own singing and it’s not bad). Perhaps he was just trying to be more “serious” with the role – goodness knows everybody else in the film was.

Either way, the material Gibson was given wasn’t exactly the most compelling stuff to begin with. John Smith has gone through the same dramatic transformation as Pocahontas; his age has been tweaked and he’s had a good shave, then apparently hit the gym for several months before getting his hair dyed and blow-dried. What was the obsession with unattainable beauty standards in this film? Smith has been bulked up into a chisel-jawed Adonis who wouldn’t look out of place on a nineties magazine cover, nothing at all like the rough-and-ready seventeenth century explorer he’s supposed to be. Originally, he was going to be a boyish redhead, but as his young friend Thomas was aged up and took on that character design for himself, Smith evolved into the blonde Errol Flynn knock-off we see in the final film. It’s nice to see that the animators seemed finally to be getting over their distaste for animating male leads, but as with Pocahontas, Smith’s looks steal the show and his actual personality (what little he has anyway) is quickly forgotten.

Critic Christopher Finch wrote that he considered John Smith “decidedly less bland” than other Disney heroes, but after seeing the likes of Beast and Aladdin in recent films, I strongly disagree. Like Pocahontas, Smith is a real step back for Disney men – he’s like one of those fifties princes, always glowering in dramatic poses but with little substance to him. What makes this worse is that John Smith is not even very likeable, especially in his early scenes.

When we first meet him, he’s the embodiment of all things macho, arriving on the Susan Constant atop a phallic cannon amidst a wave of admiration from his crewmates. Just minutes in, a huge storm blows up, giving him the chance to show off his bravado even more by rescuing the hapless Thomas. All the way to the “New World,” he continues to prattle on in an offhand way about his exploits in other lands, pillaging and attacking locals, which might very well be accurate but does little to endear him to the audience.

Like the other colonists, John starts out with no comprehension of the land he’s in or what it means to its people – he doesn’t even really see the Native Americans as people at all, in fact, talking about shooting and killing them as casually as if they were rabbits. At one point when talking about gold with Pocahontas, we get a neat little example of how different their priorities are when she presents him with an ear of corn, assuming that this is what he’s referring to because in her world food is far more valuable than a hunk of metal.

To be fair to John, he’s not as greedy as Ratcliffe and isn’t particularly motivated by the presence of gold, apparently not caring much either way whether it’s there or not as long as he gets his adventure. The real problem with him is that he starts out so arrogant and insensitive that he becomes infuriating to watch. When he first meets Pocahontas, he’s basically “hunting” her, priming his musket and leaping out of an ambush for the kill – only to be stopped when he realises how flawlessly stunning she is. It’s the sort of scene that couldn’t be made today; the heroine’s good looks actually save her life!

After the little issue of the language barrier has been hand-waved, their ensuing talk takes an ugly turn when he starts getting all “culturally superior” on her, rejecting her attempts to teach him the local greeting by saying “I like ‘hello’, better!” Yeesh, I hate that line. Is it supposed to be cute? It only gets worse when he starts dissing the local housing and then makes the fatal mistake of calling Pocahontas’s people “savages.” Naturally, at this point she’s had enough and tries to leave – but he won’t let her! Yep, our dashing hero starts trying to physically restrain the heroine and literally says to her “I’m not letting you leave!” The scene only gets more and more disturbing to watch as you get older; it’s actually worse than a similar moment from Sleeping Beauty, and that was in 1959! Remind me again why we’re supposed to like the guy?

Of course, we then get Colours of the Wind, where Pocahontas gives him the talking-to he needs and apparently persuades him to accept the error of his ways. Watching this part now, I can’t help feeling like his sudden change of heart over the course of the song feels far too quick and unnatural; he comes out of the song a totally different character! I suppose the idea is that love changes everything and his feelings for Pocahontas have opened his eyes to the Native Americans’ humanity for the first time, but it still feels a bit clunky.

It’s also interesting to note how, after the song, all talk of Smith’s “glorious” past killing other natives abroad abruptly ceases. Grandmother Willow decrees that he has a “good soul,” kindly overlooking the fact that he is a murderer and has a body count. I know girls like “bad boys,” but isn’t this a bit much? It would have been impressive if the filmmakers had had Smith grapple with some of the emotional conflict this should be causing, expressing regret or guilt over his dark past, but no – they just sweep it under the rug and make him look vaguely uncomfortable whenever someone else brings it up.

Still, I’m not being totally fair. However sudden the change is, the fact is that Smith does change, and for the rest of the film he’s a lot more palatable – except that now he’s really boring. The suppression of his trigger-happy colonist side leaves very little else and he becomes just another generic pretty-boy lead with nothing much to do until the climax, when he gets his own heroic sacrifice to compliment Pocahontas’s by saving her father from being shot. It’s good to see the progress he’s made in understanding right from wrong and at least he does get more character development than Pocahontas, but overall, I’d say he’s down there with Eric as one of the weakest Renaissance heroes. What a pity.

So, is our villain any better than our leads? Well… yes and no. For the role of Governor John Ratcliffe, Brian Cox, Rupert Everett, Stephen Fry and Sir Patrick Stewart (yet again) were all considered, but it finally went to David Ogden Stiers who had previously voiced Cogsworth and was already voicing Wiggins here. (They did also briefly consider bringing back Richard White, but felt that his voice was too distinctive and would remind people of Gaston).

As a character, Ratcliffe was based on Captain William Bligh with a design inspired by the works of William Hogarth, as well as several real English captains of the time like John Martin, Christopher Newport and Edward Maria Wingfield. In reality, Wingfield was the one who clashed with John Smith – the real Ratcliffe was actually a decent leader and helped Smith remove Wingfield from power, although he did also exploit the other colonists for labour. The filmmakers preferred the sinister sound of “Ratcliffe,” however, so Ratcliffe he became.

Although there is nothing technically wrong with him as a villain, Ratcliffe has the same problem as our main characters; he’s flat, underdeveloped and very shallow, which robs him of the complexity a good villain needs in order to be enjoyable. It doesn’t help that almost all of the Renaissance villains up to this point were compelling and highly memorable figures, with only McLeach standing out as a poor one. Originally, Ratcliffe was going to have a bit more backstory with a terror of falling back to his “commoner” roots after years of “social climbing”, but while this is hinted at in a hurried line from Wiggins, the bulk of it remains unexplored and the film version of Ratcliffe thus comes across as little more than a greedy twit.

Right from the start, it is made clear that Ratcliffe clashes with the other colonists in every way. He’s dressed in loud purples and pinks in contrast to the earthier, more natural tones of their outfits and as he boards the Susan Constant, a rat scurries up a mooring rope in the foreground in a not-too-subtle piece of foreshadowing. Much like Smith and Pocahontas, Ratcliffe’s at his best in his earlier scenes before he starts to become consumed by greedy rage. In these first few scenes, he’s quieter and more two-faced, his inner ruthlessness concealed by his foppish exterior, outwardly bolstering the men while inwardly reviling them and calling them “witless peasants.” Unfortunately, his portrayal is inconsistent and this subtlety doesn’t last long; once they’ve arrived in America, you wonder how the other colonists don’t see him for what he is sooner, as he blusters about having towering tantrums and shouting about “heathens” and gold.

There are a few hints of potential hidden depths, such as his brief moment of panic as he begins to realise that there might not be any gold after all, but these are quickly smothered as he retreats further into his stubborn delusions. This stubbornness is a big part of what makes him so unlikeable; he simply refuses to listen to anyone else’s viewpoint, childishly insisting he’s in the right even when confronted with hard evidence to the contrary.

However, the central problem with Ratcliffe is that he has a very shallow motivation, simply wanting power and money. Compared to earlier villains, many of whom were experiencing turmoil over their place in society and sought acceptance, Ratcliffe feels phoned in and lazy, and he doesn’t develop over the course of the story, winding up just as cruel and ignorant as he was at the start. The lack of proper backstory or context prevents us from understanding why he is the way he is – if only they’d left the social climbing thing in to give us an idea of the kind of pressure he’s under, and to explain his snobbery and superiority complex. Instead, we get a two-dimensional villain who is – you guessed it – boring, like so many other characters here. You can’t sympathise with him because you’re never really allowed to get to know him, but he’s not even fun to hate, because despite the campiness he’s taking himself very seriously and doesn’t seem to be particularly enjoying himself (at least outside of the musical numbers). It’s the same old theme, again and again – too serious, too boring, too flat.

It’s debatable, but the film could even have benefited from having no villain at all. With such a sensitive and complex conflict at the heart of the story, surely there was no need to simplify it into a single character like this? Many other Disney films, especially more recent ones, have dispensed with the traditional antagonist role altogether, instead allowing the circumstances of the situation to drive the stories. Having a single villain in Pocahontas might have worked well if he had had direct conflict with the main character, but Ratcliffe and Pocahontas never meet – heck, he doesn’t even see her until the climax and they never exchange any words – so there’s no compelling good guy/bad guy dynamic to enjoy. Remember Ratigan and Basil? Feels like a lifetime ago…

Among the other characters, we have Pocahontas’s father, Chief Powhatan, who is played here by Russell Means. Means was an Oglala Lakota activist and a prominent champion of Native American rights, viewing Pocahontas as a potential game-changer in Hollywood depictions of their culture. Although he initially expressed some displeasure with the script because it had the Native American characters addressing each other with proper names rather than with more traditional appellatives like “my father” or “my friend,” he was ultimately very pleased with the final film and praised it greatly in interviews, emphasising its portrayal of the colonists in a negative light and the human portrayals of the Native Americans.

It’s good to hear that he, at least, was proud of the experience, given the reactions from many other Native American critics, but unfortunately his character is no better than any of the others when it comes to personality. Powhatan is a well-meaning but overbearing father in the manner of King Triton, with no understanding of his adventurous daughter’s values and apparently little respect for her autonomy – I know it was a different time, but it’s rather jarring to hear that he’s agreed to Kocoum’s proposal on Pocahontas’s behalf before he’s even told her! “I told him it would make my heart soar!” Well, how lovely for you, but you’re not the one who’s going to be stuck with him, are you? Much like the other Renaissance dads, he also seems a tad old to be the father of such a young girl, although this is actually true to life; Powhatan did indeed father Pocahontas around the age of fifty and he was over sixty by the time in which this film takes place.

As a leader, Powhatan is fine; competent, capable and compassionate, but not especially interesting. He demonstrates a similar sense of prejudice as Ratcliffe does and is immediately suspicious of the new arrivals, although as history has shown us, he wasn’t exactly unjustified in this. He’s more open to communication than the stubborn governor, at any rate, only resorting to violence once Kocoum has been killed. Later, he is also more willing to back down and spare Smith, while Ratcliffe just wants to take advantage of the moment and continue fighting. The filmmakers were obviously trying hard to keep their portrayal “respectful”, which is certainly admirable (let’s not forget Peter Pan), but this has the side effect of rendering him inexpressive and stiff – he’s never allowed to be too funny, too angry, or too anything. All of his emotions must be kept controlled and dignified, which might keep him from offending anyone but also makes him hard to relate to.

I don’t want to repeat myself too much here, so suffice it to say that Powhatan is yet another cardboard cut-out of a character, although he is an improvement over Ratcliffe at least. If only he’d been allowed to be a bit more expressive or been given a bit more backstory, he could have been a much more memorable Disney dad.

One thing that stands out about the cast of this film is that it’s riddled with sidekicks. Smith doesn’t have as many as Pocahontas, though – his main one is a young lad called Thomas, who was gradually aged up from about twelve to seventeen after the casting of Christian Bale. The funny thing about Thomas is that he’s a bit of a dark horse and has become something of a favourite among fans, which isn’t hard to understand when comparing him with our “hero” John Smith. His youth makes him more naïve, but he’s also more likeable and relatable because he lacks the troubling past of Smith and seems to be more out of his depth on the expedition.

He reminded me a little of Simba from the last film with his childlike idea of colonialism; to him, it’s all one big adventure and he gives little thought to the more serious side of the situation, which is a real breath of fresh air in a film filled with people taking everything too seriously. Like so many real teenagers, he starts out blindly accepting whatever his older compatriots say or think, gamely trying to do everything himself but often struggling due to his lack of experience. He shares a more interesting dynamic with Ratcliffe than Smith does, with the two of them having many scenes together in which Ratcliffe degrades Thomas for his repeated failures, thus making Thomas try even harder to measure up.

All of this culminates in the scene where Thomas shoots Kocoum, combining what he’s learned from both Smith and Ratcliffe and finally stepping into the role of a colonist for real – only to find, to his horror, that he strongly disagrees with the principle of it. It’s a great moment of character development which continues to affect him in the following scenes (just watch his face in Savages as he listens to Ratcliffe’s racist dogma). In that one act, all his youthful naïveté is brutally shattered (much like Simba’s was after the death of his father) and he comes out of the experience a changed man, wiser and more self-assured. It is perhaps a bit of a stretch to have him become the new “leader” at the end, but still, it’s great to see a character with a little depth to him amidst all these lifeless mannequins. If the filmmakers had to have a romantic subplot, perhaps Thomas would have been a better match for Pocahontas? He’s closer to her age and more receptive to being taught, after all…

Thomas’s counterpart is Nakoma, who is Pocahontas’s human best friend and a rarity in the Disney canon, where heroines often spend much of their screen time alone or with animals. Michelle St. John originally auditioned for the role of Pocahontas, but was given the role of Nakoma after the casting of Irene Bedard in the title role. Nakoma represents the more constrained and conservative Native American viewpoint which Pocahontas is rebelling against – like Powhatan and Kocoum, she too is distrustful of the white colonists and is frightened for her friend when she finds out Pocahontas has been fraternising with one.

Right down to their hairstyles, the girls are complete opposites; Nakoma is much more reserved and pessimistic than Pocahontas, which is ultimately what leads her to send Kocoum after her friend later on. She’s just so fixed in her belief that the colonists mean them harm (again, though, she’s not entirely wrong). When you think about it, the whole mess at the end of the film is actually Nakoma’s fault; if she hadn’t send Kocoum after Pocahontas, Pocahontas would have taken Smith to talk to her father and perhaps avoided all the drama. Nakoma never experiences any repercussions for this though, with Powhatan even blaming Pocahontas for Kocoum’s death! (Harsh, man, harsh).

Still, like Thomas, Nakoma is a welcome addition to the cast because she adds a degree of depth that is desperately needed. I like the chemistry she and Pocahontas have; with her sassy one-liners and genuine concern for her friend, Nakoma’s presence actually adds to Pocahontas’s character by giving us a glimpse into the heroine’s daily life. The two of them feel like old friends who’ve grown up together and the scenes they share are some of the film’s more engaging ones.

For the character of Grandmother Willow, the writers originally envisioned a male being named Old Man River who would be voiced by Gregory Peck (I actually wish we could have seen that). However, Peck felt the role ought to be a more “maternal” figure and so reluctantly turned it down, leading to the gradual shift to Linda Hunt’s Grandmother Willow in the final film. This evolution was largely down to Joe Grant from the story team, who was a strong proponent of the character and pushed for her to have a bigger role. Yet even then, Katzenberg was still reluctant to use her (we know his feelings on motherly characters already) and could only be convinced to keep her in the film once she’d been given all those dreadful tree-based puns. Sigh.

Grandmother Willow is supposed to represent Pocahontas’s harmony with nature, essentially replacing the usual band of assorted forest critters (although those are still present, too). She is warm and witty for the most part, but can also be stern and serious (of course) and serves as a sort of counsellor for Pocahontas in the absence of her father’s understanding. Given the intended purpose of the character, the way Grandmother Willow is handled feels odd, but then that can be blamed on Katzenberg’s insistence on working humour in where it wasn’t needed. Willow should be dignified and insightful if she’s been around as long as she says she has, but instead she seems to serve merely as comic relief in most of her scenes. On the rare occasions when she does impart some wisdom, it’s always shrouded in “magic” or some such silliness, which already cheapens the presentation of Native American culture in the rest of the film. From what she says, Willow had a similar relationship with Pocahontas’s late mother and this could have provided her with a good reason to be in the film, connecting the two of them, but the idea never really goes anywhere.

I don’t really know what else to say about Grandmother Willow. Whenever her scenes come up I tend to switch off and wait for them to be over; she’s just as boring as most of the other characters.

Next up, we have Kocoum, who is just as dull and one-note as Pocahontas thinks he is. Solemn and unimaginative with no sense of humour, it’s easy to see why he’d be a poor match for Pocahontas. In some ways, he’s actually quite similar to John Smith – both are strong and rather overbearing men afflicted by prejudice, but Kocoum never learns (or gets the chance to learn) how to overcome it. He spends most of his screen time looking like he has a bad smell under his nose, and he shares so few scenes with Pocahontas that the two can hardly be said to have chemistry of any kind. His reaction to Smith kissing her feels more like jealousy over another man touching his “possession,” because Pocahontas has been marked out as his bride – it’s more about his rights over her than about any emotional bond he has with her.

Like Nakoma, Kocoum is a traditionalist and wants to do his bit for his people, which is certainly admirable. Unfortunately, he’s also similar to Ratcliffe in the degree of sheer stubbornness he exhibits; the wild attack on Smith is the most emotion he ever expresses, and it all stems from his uninformed belief that all the colonists are the same. After the talk from Kekata about how the white men are “ravenous wolves” out to consume resources, you wonder if Kocoum is just seeing Pocahontas as another of those resources. At any rate, Smith is clearly just another faceless enemy to be stamped out, in Kocoum’s view. He seems to be quite an angry young man, not even celebrating with the others at the start of the film after returning victorious from another battle.

It really is a problem when one member of a love triangle is so moody that you find yourself wondering if he’s suffering from depression. Why they couldn’t have allowed him even one smile I don’t know (a lot of potential scenes to develop him in were cut), but the way he’s presented makes him a difficult character to take any interest in. I agree with Pocahontas – in a film plagued with seriousness, Kocoum is the biggest victim of them all.

Kekata is the last of the Native American characters to have a significant role. In the narrative, he seems to be attempting to fill the same role as Rafiki in The Lion King, acting as the Chief’s closest confidante as well as the village shaman. However, he isn’t given the kind of charisma that Rafiki benefited from, instead being presented in the way that the filmmakers probably intended Grandmother Willow to appear – serious. (Is the word serious starting to sound weird to you yet?) In the words of critic John Grant, it is a “bitter irony” that in reality, the advice he gives Powhatan about white men turned out to be more accurate than Pocahontas’s optimistic message of equality and compassion. This is Kekata’s main function; after Namontack has been shot by Ratcliffe, Powhatan calls a village council at which Kekata uses some kind of voodoo to teach everyone about these strange new visitors. Kekata is arguably the sketchiest of the Native American characters, dancing perilously close to becoming a stereotype, but he’s not really in the film enough to create a strong impression.

The human cast is rounded out with Wiggins, Ben, Lon and Namontack. Wiggins is Ratcliffe’s personal aide and serves mostly as comic relief, delivering some genuinely funny lines with a sprightly, wide-eyed energy, but the nature of the character means there’s not much more to him than that. He feels sort of meta, as though he was the filmmakers’ way of expressing modern attitudes towards colonialism; his quick summary of the many wrongs the colonists have committed is hilariously blunt. Ultimately, since he doesn’t do anything particularly bad aside from supporting Ratcliffe, the film spares him any kind of punishment – we last see him expressing his disappointment in his fallen master.

Ben and Lon are the only other named colonists besides John and Thomas, the former with black hair in the style of Gaston and the latter a bearded redhead. Ben in particular is a highlight thanks to Billy Connolly’s spirited performance and I wish he’d had a bigger role, but Lon is less vibrant and I didn’t even know his name until I looked it up. They have some nice chemistry with each other, alternately irritable and playful, but they don’t play a big role in the story, simply giving a face to the otherwise anonymous mob of colonists and showing us their gradual loss of faith in Ratcliffe and his ideas.

Namontack has the smallest role of any of the human characters – in case you don’t remember him, he’s the dude who gets shot (apparently in the leg) by Ratcliffe during an early reconnaissance of the colonists’ camp. This is the moment where relations between the two groups begin to sour and gives the benevolent Native Americans a more solid reason to distrust the whites.

Finally, to finish up, we have three animal characters to look at (of course, it wouldn’t be Disney otherwise). As I’ve been saying, comedy was kept to a minimum in Pocahontas because they were so desperate for it to be taken seriously, which is why most of the cast in this one are humans. Joe Grant was largely responsible for creating the various animal characters we have here and there was originally going to be another one, a turkey named Redfeather who would be played by John Candy, but after Candy’s passing in March 1994 Redfeather was cut as so much of his personality relied on Candy’s style.

Of the remaining ones, Percy and Meeko are the most significant, serving as Ratcliffe and Pocahontas’s animal companions respectively. Percy is a little pug (a nod to real history as they were a popular breed with aristocrats of the day) who was going to be voiced by Richard E. Grant at first, until the decision was made to make all the animals mute. He starts out as a kind of miniature canine Ratcliffe, spoiled and greedy with no tolerance for anything that might disrupt his leisurely routine; even being ruffled affectionately by Smith annoys him. However, he meets his match in Meeko, Pocahontas’s equally greedy racoon friend who begins literally stealing food out of the dog’s mouth from the moment they get together. Like his master, Percy fiercely resists Meeko’s attempts to loosen him up at first, but the racoon’s persistence pays off and eventually (after a bit of a snap from Grandmother Willow) he grows to accept the idea of cooperating with the local animals and winds up calmer and happier by the film’s end. The relationship between the pair of them serves as a microcosm of the film’s main plot, except in their case, the “villain” learns his lesson in time.

Meeko was Redfeather’s replacement, made a racoon because characters with hands were better at pantomime (similar to Rafiki being turned from a cheetah into a primate). Meeko is one of those tricky characters that could so easily have become another Gurgi in the wrong hands, but in this case, he’s kept likeable with his brazen cheekiness and fun-loving attitude, making him the sole ray of light-heartedness in this otherwise ponderous film. Meeko’s dynamic with Percy is cute, but he also has a strange relationship with Flit, Pocahontas’s second animal sidekick and one of the film’s least necessary characters.

Meeko and Flit seem to be acting out the roles of “good angel” and “bad angel” for Pocahontas, with Meeko representing her innermost desires and the things she truly wants, while Flit represents the desires of her friends and family, i.e., the things she’s supposed to want. Flit must have been intended as a sort of Jiminy Cricket figure trying to keep Pocahontas on the straight and narrow, but with no dialogue he’s nowhere near as compelling as the former was. As it turns out, Flit just ends up serving as another embodiment of a character who’s resistant to change and wants everyone to stick to the status quo – Pocahontas herself even points out his stubbornness at one point, explaining to Smith that “Flit just doesn’t like strangers.” With Nakoma already fulfilling this role in a film loaded with sidekicks, Flit feels rather superfluous and could have easily been cut out, but then it’s not like his inclusion harms the film – indeed, he’s so inconsequential that his presence has almost no impact on it at all.

Animation

As I mentioned in my last review, Pocahontas was in production alongside The Lion King and was considered the more “prestigious” project of the two, attracting most of Disney’s top animators. Now, I may have just spent ages criticising the heck out of all the characters, but I will give them this – they all look smashing. This is some of the most realistic human animation we’ve seen so far, very subtle and nuanced and a real triumph for the artists involved. Even the directors of the film acknowledged that the level of draftsmanship required was “nothing short of brutal.” They were aided by the use of rotoscoping, for which Irene Bedard and Mel Gibson served as the models for their respective characters.

However, even here, I do have a minor criticism to make, not of the animation itself but of the character designs. Throughout the years since the film’s release, John Smith and Pocahontas have both come in for their share of criticism for being “too perfect” (especially when compared to their historical counterparts) and I have to admit, I see where people are coming from with this. Once again the controversial choice was down to Katzenberg, who ordered animator Glen Keane to make Pocahontas “the most idealised and finest woman ever made.” Apparently, Keane agreed with the necessity of this, saying at the time, “We’re doing a mature love story here, and we’ve got to draw her as such. She has to be sexy.”

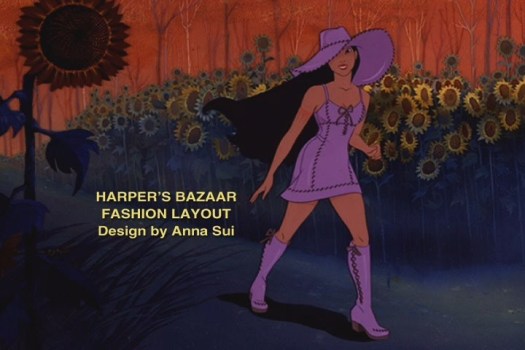

I assume he meant that the heroine needed to be sexually appealing for the audience to be able to get on board with the romance, which is a weird and rather insidious idea. After all, look at a couple like Bernard and Bianca – they’re not even human, yet we have no trouble believing in their relationship because they’re so well acted and animated. Katzenberg’s reasoning was probably more along the lines of getting the Academy interested in the film; with Hollywood dominated by white men, Pocahontas was bound to be exoticised to some extent in order to appeal to them. The best that can be said here is that at least the objectification is not gender-specific; John Smith, too, has been beefed up into a sort of seventeenth century Fabio, making this perhaps the most intimidatingly beautiful couple in the entire canon. For the June 1995 edition of Harper’s Bazaar, Pocahontas actually got her own photo spread, modelling outfits designed by Versace, Marc Jacobs, Anna Sui and Isaac Mizrahi which were then drawn by the Disney animators – I think this says a lot about the wider perception of the character. If these two were in high school, they probably wouldn’t be friends with any of us.

As the star animator and a veteran of characters as diverse as Ratigan, Ariel, Beast and Aladdin, Glen Keane was the natural choice for Pocahontas. To prepare, he studied the 1980 book Feminine Beauty by Sir Kenneth Clark to understand how ideas of female beauty have changed (or stayed the same) across history. He was also inspired by meeting two Powhatan sisters, Shirley Little Dove Custalow-McGowan and Debbie White Dove Custalow, during the 1992 trip to Virginia. Upon first being introduced, Shirley regarded Keane with a commanding confidence that left a strong impression on him, a memory he returned to when animating Pocahontas’s first meeting with John Smith (so that’s what that moment is supposed to be about). Apparently, he was further inspired by the memory of meeting his own wife in a line at a cinema and falling in love at first sight.

For her actual appearance, Keane did briefly look at portraits of the real Pocahontas, but declared that she was “not exactly a candidate for People’s ‘Most Beautiful’ issue {so} I made a few adjustments to add an Asian feeling to her face.” He also commented of the images that “She looked like someone was trying to make her white,” which could certainly be true given the time period. Keane took a little of Naomi Campbell as well as other models like Christy Turlington and Kate Moss, adding in elements of certain actresses like Charmaine Craig and Natalie Venetia Belcon, voice actress Irene Bedard and also live-action model Dyna Taylor, who got about $200 for four modelling sessions. All in all, it took a staggering fifty-five people just to design her, which may explain why the final result doesn’t look particularly Native American – she’s an ethnic smorgasbord, created with bits and pieces of at least half a dozen different women of various backgrounds… a dark-skinned Barbie doll.

One of my favourite aspects of the animation in this film is of Pocahontas’s hair. She’s hardly the first Disney girl with such a luxurious mane, but until now they’ve all had the same sort of thick mass – with Pocahontas, according to lead clean-up artist Renée Holt-Bird, her hair became “an expression of her freedom, her soulful quality,” and whatever that means, it look glorious, rippling and flowing in the wind. Of course, how she got it so sleek and shiny without the benefit of modern hair-care products is anyone’s guess, but whatever her secret is, she’s clearly doing something right – indeed, her hair is almost more interesting to watch in some scenes than she is.

Among the other characters, John Smith was supervised by none other than John Pomeroy, who was making his return to the Disney studio after more than a decade’s absence – we haven’t seen him since The Fox and the Hound, where he was among the group of animators who resigned in the wake of Don Bluth’s departure. The pompous Ratcliffe was handled largely by Duncan Marjoribanks, who moved the character’s centre of gravity up into his chest to give him a more physically threatening screen presence. For Meeko, Nik Ranieri did some highly engaging work, making the loveable little scamp a real scene-stealer, while Dave Pruiksma injected as much personality as possible into the miniscule hummingbird, Flit. Chris Buck worked with characters like Percy, Wiggins and Grandmother Willow (at least her face, which was traditionally animated), and Ruben Aquino handled the stoic Chief Powhatan (undoubtedly a challenging assignment, as the character is not exactly what you’d call ‘animated’). Nakoma and Kocoum were done by Anthony DeRosa and Michael Cedeno respectively, while Ken Duncan and T. Daniel Hofstedt rounded out the cast with Thomas, Lon and Ben.

Once again, computer animation played a part in the production, although interestingly it wasn’t really given a single standout scene in this film as it had been in the ones leading up to it. There’s no ballroom waltz, carpet ride or wildebeest stampede here – instead, the use of computer animation is actually quite understated. With the film’s CG department headed by Steve Goldberg, the effects were reserved mainly for the boats and ships, as well as for parts of Grandmother Willow; they’re some of the subtlest we’ve seen so far and it’s a point in the film’s favour, as so much CGI of the time has become incredibly dated two decades down the line.

Plot

Right, let’s just get this out of the way – the film has almost nothing in common with historical facts. Personally, I don’t think that’s as big of a problem as some critics like to make it – after all, the filmmakers never pretended that Pocahontas was going to be a documentary; they simply used one account (which may itself be a fabrication) as the basis for their own story. Wikipedia even states that “Screenwriters Carl Binder, Susannah Grant, and Philip LaZebnik took creative liberties with history in an attempt to make the film palatable to audiences.” The fact is that Pocahontas’s real life was too tragic to adapt exactly, involving kidnapping, religious conversion and an early death around the age of twenty-one, likely due to smallpox or tuberculosis. Some critics have argued that Disney should never have used her as a character at all, a point which is certainly worth debating, but for our purposes it’s enough to understand that the film was always intended as fiction.

Tom Sito, who supervised the story department, did extensive research into the historical background of the period and the people involved, so the filmmakers definitely knew the material they were working with. Director Mike Gabriel was already aware that in reality Pocahontas ended up marrying John Rolfe (after converting to Christianity and becoming Rebecca), but he explained that “the story of Pocahontas and Rolfe was too complicated and violent for a youthful audience,” which was why they ultimately chose to focus on her time with Smith. (Rolfe would be returned to in the sequel). Further problems arose when they realised how young the historical Pocahontas was when she met Smith and how unsavoury the real Smith was said to be, so producer James Pentecost admitted that dramatic license had to be taken. Glen Keane explained the age boost of Pocahontas by saying, “We had the choice of being historically accurate or socially responsible, so we chose the socially responsible side.” As I argued above, the idea of turning this particular story into a romance wasn’t the most natural or straightforward, but I am glad that they aged her up if they had to give her a love interest at all.

Roger Ebert was one of the most notable critics who called the film out for its inaccuracies, writing “Having led one of the most interesting lives imaginable, Pocahontas serves here more as a simplified symbol,” but Sito responded that, “Contrary to the popular verdict that we ignored history on the film, we tried hard to be historically correct and to accurately portray the culture of the Virginia Algonquins.” Sophie Gilbert of The Atlantic conceded that “The movie might have fudged some facts,” but this allowed it to tell “a compelling romantic story.” (How compelling this “romance” was is a different matter entirely, but I see her point).

In its final form, the story of Pocahontas bears some similarity to Romeo and Juliet (which was, as I noted in the intro, one of the early concepts for it). This feels especially appropriate given the setting in 1607, at which time the play was a recent publication and a popular show. In addition to this, the racial and environmental tones running throughout it feel distinctly “nineties,” as both were hot topics at the time in the wake of such events as the LA Riots, the beating of Rodney King, the Kuwaiti Oil Fires and the first World Oceans Day. Pocahontas had often been compared to the 1992 animated film FernGully: The Last Rainforest, which espouses a similar message of environmental protection, and more recently to James Cameron’s Avatar (2009) for the same reason.

During the production, Disney head Michael Eisner apparently pushed the idea of giving Pocahontas a mother, pointing out that “We’re always getting fried for having no mothers.” However, this was one instance where real history was actually adhered to (somewhat), with the writers pointing out that the real Powhatan was polygamous and formed dynastic alliances with neighbouring tribes by siring lots of children with their women and then giving them away, so the real Pocahontas likely didn’t see her own mother very much. “Well,” said Eisner, “I guess that means we’re toasted.” The idea of the mother’s “spirit” was eventually incorporated in the swirling multi-coloured leaves seen throughout the film (it’s easy to miss, but they’re supposed to indicate her presence).

One other recurring criticism of the film is of the whole language barrier issue and let’s be honest, “listening with one’s heart” really is cheesy and contrived. The thing is, unless you’re dealing specifically in myths and legends, Native Americans themselves are not “magical.” While harmony with nature and the seasons is a big part of most Native American cultures, the filmmakers take this concept to ludicrous lengths by presenting them almost as deities, able to do any number of foolhardy things (like jumping off hundred-foot cliffs and stealing bear cubs from their mothers) with no consequences whatsoever. Pocahontas suddenly developing the skills of Google Translate by “listening with her heart” is just the icing on the cake – it’s lazy and mildly insulting, both to Native Americans and to the audience.

However, while I do hate that part, one part of the film that I love is the final parting of Smith and Pocahontas. This film may well have a lot wrong with it, but I’ve always considered the ending to be one of Disney’s strongest because it’s just so different from the usual clichéd “happy ending” that they tend to go with. By having the heroine make the more mature choice to stay with her loved ones instead of abandoning them to be a with a man she’s just met, Pocahontas fixes the problem with the ending of The Little Mermaid, where Ariel does the exact opposite. Of course, it might not quite fit Pocahontas’s adventurous character as it’s presented here, but it does feel more interesting from a narrative perspective. It was a bold choice on Disney’s part to acknowledge that real life isn’t always rosy and perfect and that hard choices sometimes have to be made – I respect that, and the ending is thus one of the film’s saving graces (at least for me).

Before we move on, I also want to look for a moment at an interesting point made by critic Lindsay Ellis in a recent video essay. She points out the startling number of similarities between Pocahontas and last year’s Moana, which are so numerous that you start to see why she describes the latter as a “stealth remake” of Pocahontas. Both films focus on a group of indigenous people living in pre-colonial times, with a heroine who is the daughter of the local Chief. Both girls have an affinity for water and get a whole song about their relationship to it (humorously parodied at the end of Ellis’s video with Water is the Metaphor, to the tune of Just Around the Riverbend). They also each have a grandmotherly figure in their lives who possesses a vague “spiritual” insight that nobody else in the tribe has, and both heroines must face a conflict which comes from over the sea, as well as a treasure-obsessed antagonist. They are both joined by disrespectful men who must learn to treat them as equals, and both girls make a big mistake at one point which nearly results in their companion’s death. Crucially, both also have a moment of self-doubt in which they are given advice by their spirit-grandmas, with both ultimately saving the day through compassion rather than violence.

The key thing Ellis points out in the comparison is that Moana handles the story much better than Pocahontas, chiefly because her motivations are clearer and stronger than Pocahontas’s and she goes through significantly more character development. Where Pocahontas is motivated by vague “dreams” and the urgings of Grandmother Willow, Moana is motivated by her own passion for her culture and the desire to protect her homeland. When Moana is having her self-doubt moment and talks with her spirit-grandma, there’s a big difference from the same scene in Pocahontas – in Moana, the grandma reassures Moana that there is no shame in calling it a day and going home, supporting her in whatever she chooses and leaving the way open for Moana to come to her own realisation; to choose to continue of her own volition. In Pocahontas’s case, Grandmother Willow is basically ordering her to go and rescue Smith whether she wants to or not, because it’s “her path.” It’s good to see that Disney learned from their experiences on Pocahontas and improved upon this story the second time round, but as it is here, it’s a shame to see that the heroine has such restricted autonomy.

(It’s also cool that Moana doesn’t include a forced romantic subplot!)

Cinematography

If you’re a fan of this film, you must hate me by now – I have been criticising it a lot, but I swear the next two sections will be kinder. Pocahontas might not have the strongest characters or the best story, but one thing’s for sure: it looks absolutely fabulous. Rasoul Azadani was once again the head of layout, while Cristy Maltese led the background department and Don Paul managed the special effects team from California (Jeff Dutton did the same at the Florida studio).To create the film’s distinctive look, art director Michael Giaimo sought inspiration from some of Disney’s earlier films like Sleeping Beauty (1959) with its stylised Eyvind Earle backgrounds and delicate palette, as well as from story sketches by Richard Kelsey from the unproduced film Hiawatha (a short version was made in 1937). The artists also drew inspiration from the sketches of artists from early European expeditions to the Americas, such as John White and Jacques le Moyne de Morgues (both of whom died before Pocahontas was born).

There are some nice historical touches within the film which add to the authenticity of the setting. The ship the colonists use to reach the Americas, the Susan Constant, was indeed one of those used on that particular voyage to Virginia, although in reality it was accompanied by two others: the Discovery and the Godspeed. Jean Gillmore from the art department spent months researching for the costumes to try and ensure period accuracy, and the weapons used by the colonists are also period-appropriate matchlock muskets. Critics often seem to bring up the issue of the English flag Ratcliffe plants upon founding Jamestown, saying that it is incorrect for the time, but as far as I can determine the design actually is accurate – the Union Jack was introduced just the previous year by King James I for specific use on ships, becoming adopted as the national flag almost a century later in 1707, so it is (just barely) correct after all.

With Pocahontas, it is the attention to details like these that really make the film stand out visually from its neighbours in the canon. I like the opening, with an old-fashioned painting fading into an establishing shot of Shakespearian London, although it must be said that it doesn’t compare with the opening of the “B” squad’s film (to be fair, few films top The Lion King’s opener). We also get a few clever shots for foreshadowing, like the one of Ratcliffe boarding the ship with a rat scurrying along in parallel in the foreground in this first scene.

Lighting and colour were used carefully throughout the film to emphasise the emotional beats of the story; for instance, red and similar shades were reserved for Ratcliffe and nobody else wears them, but by the time we get to Savages the entire palette is awash with it as the anger and bloodlust mounts.

As I mentioned above, the swirling leaves which appear throughout the film were intended to represent the spirit of Pocahontas’s mother (although this isn’t made particularly clear). Don Paul explained the details they included even in this seemingly minor effect, saying “We put subtle Indian hieroglyphic shapes sparkling in the wind and based the leaves on Native American graphic shapes, especially arrowheads.” These can be spotted in some shots, if you have a keen eye!

One aspect of the cinematography which everybody likes to bring up is the staging. It’s almost comically strong throughout the film, with everybody standing about making dramatic poses atop towering cliffs all the time (you wonder if there was a little envy of the “B” squad’s work going on here). Giaimo stated that he “was after a Shangri-La version of Virginia, a paradise found.” The version of coastal Virginia we see in the film might not be realistic, but it does look very grand and cinematic, shrouded in mist with a palette full of dreamy blues and purples. Some of the quieter moments also feature strong staging, however corny it might feel at times – Smith and Pocahontas’s first meeting by the waterfall is powerfully done, and I like the use of perspective shots later on when Kocoum and Thomas are spying on the kissing couple. However, nothing beats the climax, where the Native Americans are positioned high above the white colonists on a huge promontory in a very literal representation of occupying the moral “high ground.”

The editing of the film is generally quite fast and tight, which is sometimes frustrating because it prevents you from fully appreciating the magnificent backgrounds on display. This “MTV” style does work well during the climactic scenes, though, setting pulses racing as the two opposing sides march towards one another while Pocahontas hurries to stop them (then again, the slow-mo overlays are just as hokey here as they were in The Lion King).

As always, the artistic highlights are the musical numbers, particularly Colours of the Wind, where the artists surpassed themselves with their appropriately colourful depictions of Pocahontas’s world, but we’ll get into those in more detail in the final section.

Soundtrack

Pocahontas doesn’t just look beautiful; it sounds beautiful too. The music is the one other aspect of it which even its harshest critics generally agree is superb. Originally, Howard Ashman was going to be involved with this production once he’d finished his work on the many others he was involved with, but sadly, his death in 1991 prevented this and he never created a single piece for Pocahontas. What could have been, eh? Still, it’s not like we have room to complain, because even without him this remains one of Disney’s most fantastic soundtracks.

For this film, Stephen Schwartz was brought in as lyricist, apparently because he was more convenient for composer Alan Menken to work with than the perpetually-wandering Tim Rice, since he lived in New York like Menken. It was a tougher collaboration than Menken’s last, however; he commented on the tension he and Schwartz experienced while working together because both were capable songwriters and composers in their own right, which meant they were both itching to use the keyboard. Luckily, they were able to work out a good working strategy. Menken would write the melody with Schwartz listening and making suggestions at the piano, then Schwartz would add lyrics before their next session together, at which they would be refined and perfected.

Schwartz accompanied the artists on their 1992 trip to Jamestown, where he absorbed the atmosphere of the place and bought tapes of everything from Native American music to English sea shanties, as well as other pieces of music from the early 1600s, which all helped to inspire the numbers for the film. (It’s worth noting that the songs couldn’t easily be written in Powhatan, not just because the language itself is extinct but because Native American music often consists entirely of vocables, which are lyrics with no linguistic meaning).

As always, Menken’s score is a delight, kept light and poetic here to match the overall feel of the film. Some of the standout moments are the first meeting of Smith and Pocahontas and especially the final scene where the two are parted – the music here, simply titled Farewell, is truly the making of that scene and puts a lump in my throat every time. It’s arguably not his best Renaissance-era score (just you wait until next week), but it’s certainly a strong one all the same.

The opening number, Virginia Company, is no Circle of Life, but it’s fine enough, setting the scene nicely and explaining the motivations of the colonists. “Glory, God and Gold” feels a bit more typical of a Spanish conquistador than an English settler, though! In a soundtrack this good, this little number was never going to be the highlight – it reminds me of Fathoms Below from Little Mermaid.

The end of the piece segues neatly into the next short number, Steady as the Beating Drum, which introduces the Native Americans and their way of life. It functions rather like Where You Are from Moana except it’s far less catchy, but it’s still a pleasant song and I feel like it’s rather underrated by fans of the film. The soothing, natural melody makes a stark contrast to the more forceful and militaristic Virginia Company, and the melodies of both pieces recur throughout the score as motifs for the two groups.

Grandmother Willow’s theme is Listen With Your Heart and it’s probably the most forgettable of the film’s songs, only really notable for featuring a line in actual Algonquin – “Que, que, natora” means “Now I understand.” Let’s get onto the big guns here!

I may be a little biased towards this one; Just Around the Riverbend may be my favourite Disney song of all time. In an earlier post, I chose it as my third favourite song from an animated film overall (behind Deliver Us from The Prince of Egypt and Journey to the Past from Anastasia). It’s so passionately performed and feels very uplifting, with Judy Kuhn’s sensational voice positively bursting with energy. Just try singing along to it and see if it doesn’t put you in a better mood! Astoundingly, this was another one of those songs that was nearly dropped because the Disney executives didn’t like it at first, but thankfully Menken and Schwartz believed in it and fought to keep it in. Schwartz described the song as “the Native American version of Something’s Coming {from West Side Story}”, so this is one of the many Disney classics to have been inspired by the world of musical theatre.

The song is performed by Pocahontas quite early in the film before she’s met Smith, serving as her “I Want” song and showcasing Kuhn’s marvellous vocal range and vibrato. It feels a lot like Belle’s reprise of, well, Belle in Beauty and the Beast; both girls are unsure what exactly they want, only knowing that they want more than their current life is offering them. Apparently, Schwartz’s wife Carole conceived the idea for the song and suggested the idea of Pocahontas’s dream (ah, so that’s where that came from!). Dreams play a large part in many Native American cultures, but it’s a shame this idea wasn’t better handled by the writers because it comes across as rather contrived in the film. Still, it’s a strong moment and Pocahontas is really at her best here, lively and energetic – if only she could have remained this way for the rest of the film!

Mine, Mine, Mine, Ratcliffe’s big showstopper, has grown on me over time with its bold theatrical style. David Ogden Stiers has a better voice than people give him credit for! I chose this one as my ninth favourite animated villain song in an earlier post, noting that the song is far more enjoyable than the villain who sings it, ironically. Given how underdeveloped Ratcliffe’s character is, this song is one of the few moments where we get even a glimpse of his deeper motivations, learning about his political ambitions and his reasoning for assuming gold will even be in Virginia in the first place (it’s the fault of the Spanish). He quickly sets all of the other men off digging while not lifting a finger himself, making excuses about his spine and other such nonsense when he’s clearly one of the largest and strongest men in the company. The little fantasy segment where he dreams of overthrowing the King (seriously) has become a popular meme, with Ratcliffe descending the stairs draped in glittering gold – his line about having the ladies “all a-twitter” isn’t fooling anyone, he’s far too self-absorbed to ever fall in love with anyone but himself!

The other interesting thing about this as a villain song is that Ratcliffe shares it with John Smith, who joins in halfway through with a few verses about his very different perspective on this New World; he wants to explore it rather than dig it up, telling us with all the subtlety of an anvil that we’re supposed to be rooting for him because hey, he’s not greedy. And he’s not wearing pigtails with little bows on them.

There’s some great brass and woodwind featured in this hammy song, but the best thing about it is probably the staging – there are some excellent shots of “Virginia” (or the filmmakers’ very dramatic impression of it, anyway), culminating in a mass of fiery explosions as Ratcliffe blows it all to kingdom come.